Why transformative AI is really, really hard to achieve

2023-06-27 13:38 BST

Joint with Arjun Ramani. Originally published in The Gradient.

A collection of the best technical, social, and economic arguments

Humans have a good track record of innovation. The mechanization of agriculture, steam engines, electricity, modern medicine, computers, and the internet—these technologies radically changed the world. Still, the trend growth rate of GDP per capita in the world’s frontier economy has never exceeded three percent per year.

It is of course possible for growth to accelerate.1 There was time before growth began, or at least when it was far closer to zero. But the fact that past game-changing technologies have yet to break the three percent threshold gives us a baseline. Only strong evidence should cause us to expect something hugely different.

Yet many people are optimistic that artificial intelligence is up to the job. AI is different from prior technologies, they say, because it is generally capable—able to perform a much wider range of tasks than previous technologies, including the process of innovation itself. Some think it could lead to a “Moore’s Law for everything,” or even risks on on par with those of pandemics and nuclear war. Sam Altman shocked investors when he said that OpenAI would become profitable by first inventing general AI, and then asking it how to make money. Demis Hassabis described DeepMind’s mission at Britain’s Royal Academy four years ago in two steps: “1. Solve Intelligence. 2. Use it to solve everything else.”

This order of operations has powerful appeal.

Should AI be set apart from other great inventions in history? Could it, as the great academics John Von Neumann and I.J. Good speculated, one day self-improve, cause an intelligence explosion, and lead to an economic growth singularity?

Neither this essay nor the economic growth literature rules out this possibility. Instead, our aim is to simply temper your expectations. We think AI can be “transformative” in the same way the internet was, raising productivity and changing habits. But many daunting hurdles lie on the way to the accelerating growth rates predicted by some.

In this essay we assemble the best arguments for why transformative AI is hard to achieve. We are far from the first to suggest these points. To avoid lengthening an already long piece, we often refer to the original sources instead of reiterating their arguments in depth. Our contribution is to organize a well-researched, multidisciplinary set of ideas others first advanced into a single integrated case. Here is a brief outline of our argument:

- The transformational potential of AI is constrained by its hardest problems

- Despite rapid progress in some AI subfields, major technical hurdles remain

- Even if technical AI progress continues, social and economic hurdles may limit its impact

1. The transformative potential of AI is constrained by its hardest problems

Visions of transformative AI start with a system that is as good as or better than humans at all economically valuable tasks. A review from Harvard’s Carr Center for Human Rights Policy notes that many top AI labs explicitly have this goal. Yet measuring AI’s performance on a predetermined set of tasks is risky—what if real world impact requires doing tasks we are not even aware of?

Thus, we define transformative AI in terms of its observed economic impact. Productivity growth almost definitionally captures when a new technology efficiently performs useful work. A powerful AI could one day perform all productive cognitive and physical labor. If it could automate the process of innovation itself, some economic growth models predict that GDP growth would not just break three percent per capita per year—it would accelerate.

Such a world is hard to achieve. As the economist William Baumol first noted in the 1960s, productivity growth that is unbalanced may be constrained by the weakest sector. To illustrate this, consider a simple economy with two sectors, writing think-pieces and constructing buildings. Imagine that AI speeds up writing but not construction. Productivity increases and the economy grows. However, a think-piece is not a good substitute for a new building. So if the economy still demands what AI does not improve, like construction, those sectors become relatively more valuable and eat into the gains from writing. A 100x boost to writing speed may only lead to a 2x boost to the size of the economy.2

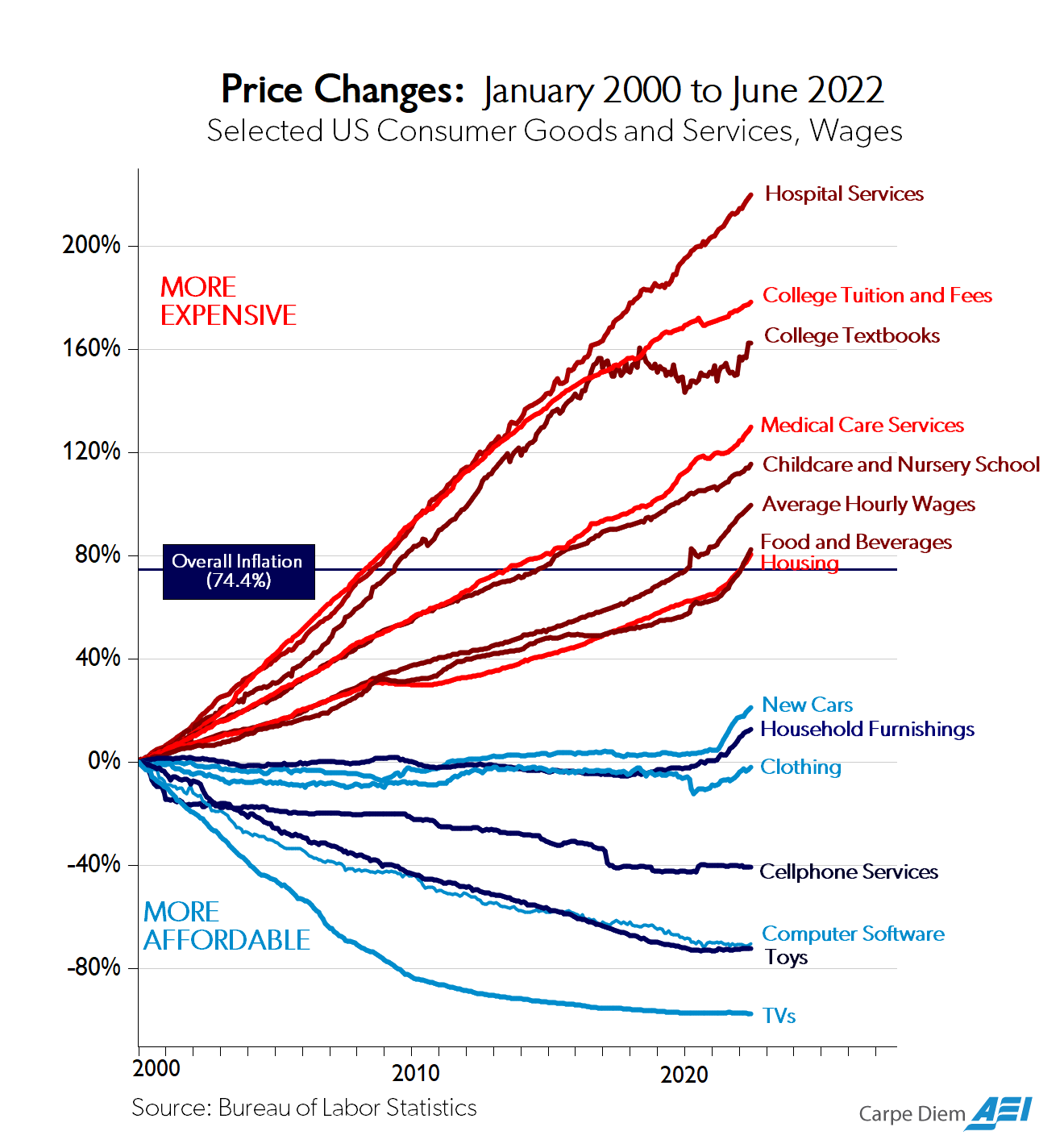

This toy example is not all that different from the broad pattern of productivity growth over the past several decades. Eric Helland and Alex Tabarrok wield Baumol in their book Why Are the Prices So Damn High? to explain how technology has boosted the productivity of sectors like manufacturing and agriculture, driving down the relative price of their outputs, like TVs and food, and raising average wages. Yet TVs and food are not good substitutes for labor-intensive services like healthcare and education. Such services have remained important, just like constructing buildings, but have proven hard to make more efficient. So their relative prices have grown, taking up a larger share of our income and weighing on growth. Acemoglu, Autor, and Patterson confirm using historical US economic data that uneven innovation across sectors has indeed slowed down aggregate productivity growth.3

Aghion, Jones, and Jones explain that the production of ideas itself has steps which are vulnerable to bottlenecks.4 Automating most tasks has very different effects on growth than automating all tasks:

…economic growth may be constrained not by what we do well but rather by what is essential and yet hard to improve… When applied to a model in which AI automates the production of ideas, these same considerations can prevent explosive growth.

Consider a two-step innovation process that consists of summarizing papers on arXiv and pipetting fluids into test tubes. Each step depends on the other. Even if AI automates summarizing papers, humans would still have to pipette fluids to write the next paper. (And in the real world, we would also need to wait for the IRB to approve our grants.) In “What if we could automate invention,” Matt Clancy provides a final dose of intuition:

Invention has started to resemble a class project where each student is responsible for a different part of the project and the teacher won’t let anyone leave until everyone is done… if we cannot automate everything, then the results are quite different. We don’t get acceleration at merely a slower rate—we get no acceleration at all.

Our point is that the idea of bottlenecking—featured everywhere from Baumol in the sixties to Matt Clancy today—deserves more airtime.5 It makes clear why the hurdles to AI progress are stronger together than they are apart. AI must transform all essential economic sectors and steps of the innovation process, not just some of them. Otherwise, the chance that we should view AI as similar to past inventions goes up.

Perhaps the discourse has lacked specific illustrations of hard-to-improve steps in production and innovation. Fortunately many examples exist.

2. Despite rapid progress in some AI subfields, major technical hurdles remain

Progress in fine motor control has hugely lagged progress in neural language models. Robotics workshops ponder what to do when “just a few cubicles away, progress in generative modeling feels qualitatively even more impressive.” Moravec’s paradox and Steven Pinker’s 1994 observation remain relevant: “The main lesson of thirty-five years of AI research is that the hard problems are easy and the easy problems are hard.” The hardest “easy” problems, like tying one’s shoelaces, remain. Do breakthroughs in robotics easily follow those in generative modeling? That OpenAI disbanded its robotics team is not a strong signal.

It seems highly unlikely to us that growth could greatly accelerate without progress in manipulating the physical world. Many current economic bottlenecks, from housing and healthcare to manufacturing and transportation all have a sizable physical-world component.

The list of open research problems relevant to transformative AI continues. Learning a causal model is one. Ortega et al. show a naive case where a sequence model that takes actions can experience delusions without access to a causal model.6 Embodiment is another. Murray Shanahan views cognition and having a body as inseparable: cognition exists for the body to survive and thrive, continually adjusts within a body’s sensorimotor loop, and is itself founded in physical affordances. Watching LeBron James on the court, we are inclined to agree. François Chollet believes efficiency is central, since “unlimited priors or experience can produce systems with little-to-no generalization power.” Cremer and Whittlestone list even more problems on which technical experts do not agree.

More resources are not guaranteed to help. Ari Allyn-Feuer and Ted Sanders suggest in “Transformative AGI by 2043 is <1% likely” that walking and wriggling (neurological simulation of worms) are simple but still intractable indicator tasks: “And while worms are not a large market… we’ve comprehensively failed to make AI walkers, AI drivers, or AI radiologists despite massive effort. This must be taken as a bearish signal.”

We may not need to solve some or even all of these open problems. And we could certainly make more breakthroughs (one of us is directly working on some of these problems). But equally, we cannot yet definitively dismiss them, thus adding to our bottlenecks. Until AI gains these missing capabilities, some of which even children have, it may be better to view them as tools that imitate and transmit culture, rather than as general intelligences, as Yiu, Kosoy, and Gopnik propose.

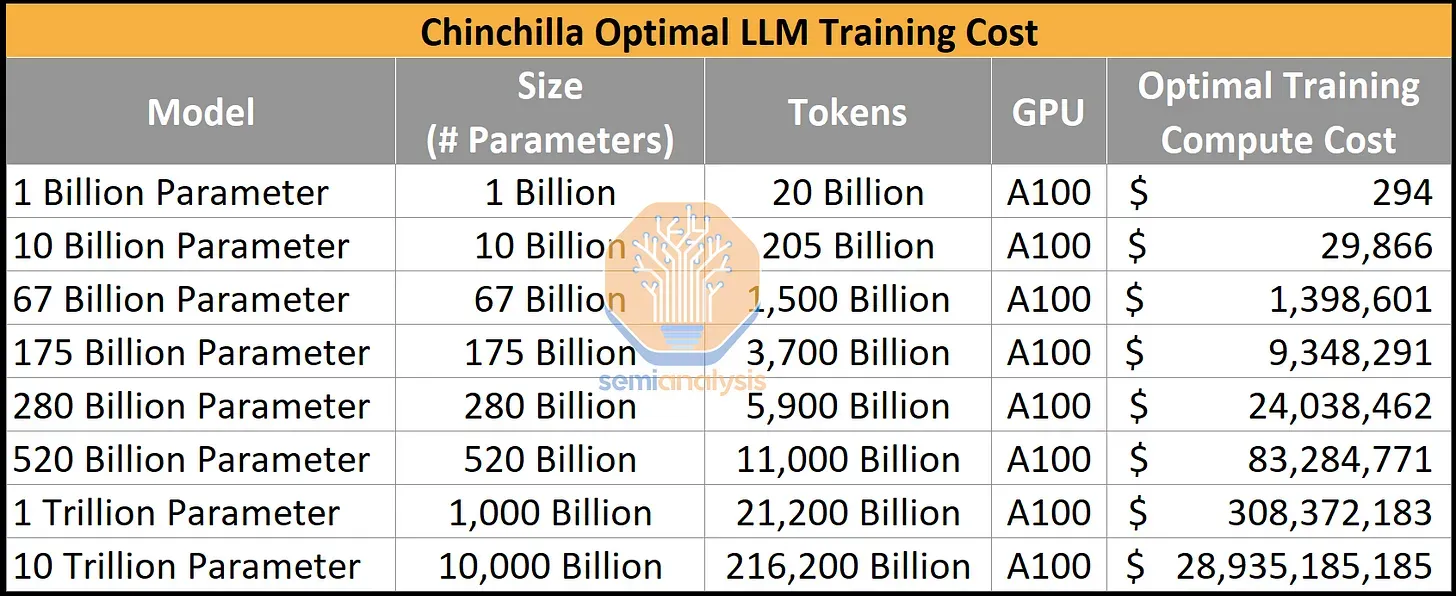

Current methods may also not be enough. Their limits may soon be upon us. Scaling compute another order of magnitude would require hundreds of billions of dollars more spending on hardware. According to SemiAnalysis: “This is not practical, and it is also likely that models cannot scale to this scale, given current error rates and quantization estimates.” The continued falling cost of computation could help. But we may have exhausted the low-hanging fruit in hardware optimization and are now entering an era of deceleration. Moore’s Law has persisted under various guises, but the critical factor for transformative AI may be whether we will reach it before Moore’s Law stops.

Next look at data. Villalobos et al. warns that high quality language data may run out by 2026. The team suggests data efficiency and synthetic data as ways out, but so far these are far from complete solutions as Shumailov et al. shows.

In algorithms, our understanding of what current architectures can and cannot do is improving. Delétang et al. and Dziri et al. identify particularly hard problems for the Transformer architecture. Some say that so-called emergent abilities of large language models could still surprise us. Not necessarily. Schaeffer et al. argues that emergence appears “due the researcher’s choice of metric rather than due to fundamental changes in model behavior with scale.” We must be careful when making claims about the irregularity of future capabilities. It is telling that OpenAI will not train GPT-5 for some time. Perhaps they realize that good old-fashioned human tinkering is more appetizing than a free lunch of scale.

Humans remain a limiting factor in development. Human feedback makes AI outputs more helpful. Insofar as AI development requires human input, humans will constrain productivity. Millions of humans currently annotate data to train models. Their humanity, especially their expert knowledge and creative spark, becomes more valuable by the day. The Verge reports: “One engineer told me about buying examples of Socratic dialogues for up to $300 a pop.”

That is unlikely to change anytime soon. Geoffrey Irving and Amanda Askell advocate for a bigger role for humans: “Since we are trying to behave in accord with people’s values, the most important data will be data from humans about their values.” Constitutional AI, a state-of-the-art alignment technique that has even reached the steps of Capitol Hill, also does not aim to remove humans from the process at all: “rather than removing human supervision, in the longer term our goal is to make human supervision as efficacious as possible.” Even longer-term scalable alignment proposals, such as running AI debates with human judges, entrenches rather than removes human experts. Both technical experts and the public seem to want to keep humans in the loop.

A big share of human knowledge is tacit, unrecorded, and diffuse. As Friedrich Hayek declared, “To assume all the knowledge to be given to a single mind… is to assume the problem away and to disregard everything that is important and significant in the real world.” Michael Polanyi argued: “that we can know more than we can tell.” Carlo Ginzburg concurred: “Nobody learns how to be a connoisseur or a diagnostician simply by applying the rules. With this kind of knowledge there are factors in play which cannot be measured: a whiff, a glance, an intuition.” Finally, Dan Wang, concretely:

Process knowledge is the kind of knowledge that’s hard to write down as an instruction. You can give someone a well-equipped kitchen and an extraordinarily detailed recipe, but unless he already has some cooking experience, we shouldn’t expect him to prepare a great dish.

Ilya Sutskever recently suggested asking an AI “What would a person with great insight, wisdom, and capability do?” to surpass human performance. Tacit knowledge is why we think this is unlikely to work out-of-the-box in many important settings. It is why we may need to deploy AI in the real world where it can learn-by-doing. Yet it is hard for us to imagine this happening in several cases, especially high-stakes ones like running a multinational firm or teaching a child to swim.

We are constantly surprised in our day jobs as a journalist and AI researcher by how many questions do not have good answers on the internet or in books, but where some expert has a solid answer that they had not bothered to record. And in some cases, as with a master chef or LeBron James, they may not even be capable of making legible how they do what they do.

The idea that diffuse tacit knowledge is pervasive supports the hypothesis that there are diminishing returns to pure, centralized, cerebral intelligence. Some problems, like escaping game-theoretic quagmires or predicting the future, might be just too hard for brains alone, whether biological or artificial.

We could be headed off in the wrong direction altogether. If even some of our hurdles prove insurmountable, then we may be far from the critical path to AI that can do all that humans can. Melanie Mitchell quotes Stuart Dreyfus in “Why AI is Harder Than We Think”: “It was like claiming that the first monkey that climbed a tree was making progress towards landing on the moon.”

We still struggle to concretely specify what we are trying to build. We have little understanding of the nature of intelligence or humanity. Relevant philosophical problems, such as the grounds of moral status, qualia, and personal identity, have stumped humans for thousands of years. Just days before this writing, neuroscientist Christof Koch lost a quarter-century bet to philosopher David Chalmers that we would have discovered how the brain achieves consciousness by now.

Thus, we are throwing dice into the dark, betting on our best hunches, which some believe produce only stochastic parrots. Of course, these hunches are still worth pursuing; Matt Botvinick explores in depth what current progress can tell us about ourselves. But our lack of understanding should again moderate our expectations. In a prescient opinion a decade ago, David Deutsch stressed the importance of specifying the exact functionality we want:

The very term “AGI” is an example of one such rationalization, for the field used to be called “AI”— artificial intelligence. But AI was gradually appropriated to describe all sorts of unrelated computer programs such as game players, search engines and chatbots, until the G for “general” was added to make it possible to refer to the real thing again, but now with the implication that an AGI is just a smarter species of chatbot.

A decade ago!

3. Even if technical AI progress continues, social and economic hurdles may limit its impact

The history of economic transformation is one of contingency. Many factors must come together all at once, rather than one factor outweighing all else. Individual technologies only matter to the extent that institutions permit their adoption, incentivize their widespread deployment, and allow for broad-scale social reorganization around the new technology.

A whole subfield studies the Great Divergence, how Europe overcame pre-modern growth constraints. Technological progress is just one factor. Kenneth Pommeranz, in his influential eponymous book, argues also for luck, including a stockpile of coal and convenient geography. Taisu Zhang emphasizes social hierarchies in The Laws and Economics of Confucianism. Jürgen Osterhammel in The Transformation of the World attributes growth in the 19th century to mobility, imperial systems, networks, and much more beyond mere industrialization: “it would be unduly reductionist to present [the organization of production and the creation of wealth] as independent variables and as the only sources of dynamism propelling the age as a whole… it is time to decenter the Industrial Revolution.”

All agree that history is not inevitable. We think this applies to AI as well. Just as we should be skeptical of a Great Man theory of history, we should not be so quick to jump to a Great Technology theory of growth with AI.

And important factors may not be on AI’s side. Major drivers of growth, including demographics and globalization, are going backwards. AI progress may even be accelerating the decoupling of the US and China, reducing the flow of people and ideas.

AI may not be able to automate precisely the sectors most in need of automation. We already “know” how to overcome many major constraints to growth, and have the technology to do so. Yet social and political barriers slow down technology adoption, and sometimes halt it entirely. The same could happen with AI.

Comin and Mestieri observe that cross-country variation in the intensity of use for new technologies explains a large portion of the variation in incomes in the twentieth century. Despite the dream in 1954 that nuclear power would cause electricity to be “too cheap to meter,” nuclear’s share of global primary energy consumption has been stagnant since the 90s. Commercial supersonic flight is outright banned in US airspace. Callum Williams provides more visceral examples:

Train drivers on London’s publicly run Underground network are paid close to twice the national median, even though the technology to partially or wholly replace them has existed for decades. Government agencies require you to fill in paper forms providing your personal information again and again. In San Francisco, the global center of the AI surge, real-life cops are still employed to direct traffic during rush hour.

Marc Andreessen, hardly a techno-pessimist, puts it bluntly: “I don’t even think the standard arguments are needed… AI is already illegal for most of the economy, and will be for virtually all of the economy. How do I know that? Because technology is already illegal in most of the economy, and that is becoming steadily more true over time.” Matt Yglesias and Eli Dourado are skeptical that AI will lead to a growth revolution, pointing to regulation and complex physical processes in sectors including housing, energy, transportation, and healthcare. These happen to be our current growth bottlenecks, and together they make up over a third of US GDP.

AI may even decrease productivity. One of its current largest use cases, recommender systems for social media, is hardly a productivity windfall. Callum Williams continues:

GPT-4 is a godsend for a NIMBY facing a planning application. In five minutes he can produce a well written 1,000-page objection. Someone then has to respond to it… lawyers will multiply. “In the 1970s you could do a multi-million-dollar deal on 15 pages because retyping was a pain in the ass,” says Preston Byrne of Brown Rudnick, a law firm. “AI will allow us to cover the 1,000 most likely edge cases in the first draft and then the parties will argue over it for weeks.”

Automation alone is not enough for transformative economic growth. History is littered with so-so technologies that have had little transformative impact, as Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson note in their new book Power and Progress. Fast-food kiosks are hardly a game-changer compared to human employees. Nobel laureate Robert Fogel documented that in the same way, railroads had little impact on growth because they were only a bit better than their substitutes, canals and roads. Many immediate applications of large language models, from customer service to writing marketing copy, appear similar.7

OpenAI’s own economists estimate that about “19% of jobs have at least 50% of their tasks exposed” to GPT-4 and the various applications that may be built upon it. Some view this as game-changing. We would reframe it. That means over 80% of workers would have less than 50% of their tasks affected, hardly close to full automation. And their methodology suggests that areas where reliability is essential will remain unaffected for some time.

It is telling that though the investment services sector is digitized, data is ubiquitous, and many individual tasks are automated, overall employment has increased. Similarly, despite predictions that AI will replace radiologists (Hinton: “stop training radiologists now”), radiology job postings hit a record high in 2021 and is projected to increase even more. Allyn-Feuer and Sanders reviewed 31 predictions of self-driving by industry insiders since 1960. The 27 resolved predictions were all wrong. Eight were by Elon Musk. In all these cases, AI faces the challenge of automating the “long tail” of tasks that are not present in the training data, not always legible, or too high-stakes to deploy.

A big share of the economy may already consist of producing output that is profoundly social in nature. Even if AI can automate all production, we must still decide what to produce, which is a social process. As Hayek once implied, central planning is hard not only because of its computational cost, but also due to a “lack of access to information… the information does not exist.” A possible implication is that humans must actively participate in business, politics, and society to determine how they want society to look.

Education may be largely about motivating students, and teaching them to interact socially, rather than just transmitting facts. Much of the value of art comes from its social context. Healthcare combines emotional support with more functional diagnoses and prescriptions. Superhuman AI can hardly claim full credit for the resurgence of chess. And business is about framing goals and negotiating with, managing, and motivating humans. Maybe our jobs today are already not that different from figuring out what prompts to ask and how to ask them.

There is a deeper point here. GDP is a made-up measure of how much some humans value what others produce, a big chunk of which involves doing social things amongst each other. As one of us recently wrote, we may value human-produced outputs precisely because they are scarce. As long as AI-produced outputs cannot substitute for that which is social, and therefore scarce, such outputs will command a growing “human premium,” and produce Baumol-style effects that weigh on growth.

How should we consider AI in light of these hurdles?

AI progress is bound to continue and we are only starting to feel its impacts. We are hopeful for further breakthroughs from more reliable algorithms to better policy. AI has certainly surprised us before.

Yet as this essay has outlined, myriad hurdles stand in the way of widespread transformative impact. These hurdles should be viewed collectively. Solving a subset may not be enough. Solving them all is a combinatorially harder problem. Until then, we cannot look to AI to clear hurdles we do not know how to clear ourselves. We should also not take future breakthroughs as guaranteed—we may get them tomorrow, or not for a very long time.

The most common reply we have heard to our arguments is that AI research itself could soon be automated. AI progress would then explode, begetting a powerful intelligence that would solve the other hurdles we have laid out.

But that is a narrow path to tread. Though AI research has made remarkable strides of late, many of our hurdles to transformation at large apply to the process of automating AI research itself. And even if we develop highly-intelligent machines, that is hardly all that is needed to automate the entirety of research and development, let alone the entire economy. To build an intelligence that can solve everything else, we may need to solve that same everything else in the first place.

So the case that AI will be an invention elevated far above the rest is not closed. Perhaps we should best think of it as a “prosaic” history-altering technology, one that catalyzes growth on the order of great inventions that have come before. We return to the excellent Aghion, Jones, and Jones:

…we model A.I. as the latest form in a process of automation that has been ongoing for at least 200 years. From the spinning jenny to the steam engine to electricity to computer chips, the automation of aspects of production has been a key feature of economic growth since the Industrial Revolution.

Recall, the steam engine is general, too. You may not think it is as general as a large language model. But one can imagine how turning (the then infinite) bits of coal into energy would prompt a nineteenth century industrialist to flirt with the end of history.

The steam engine certainly increased growth and made the world an unrecognizable place. We want to stress that AI ending up like the steam engine, rather than qualitatively surpassing it, is still an important and exciting outcome! What then to make of AI?

The most salient risks of AI are likely to be those of a prosaic powerful technology. Scenarios where AI grows to an autonomous, uncontrollable, and incomprehensible existential threat must clear the same difficult hurdles an economic transformation must. Thus, we believe AI’s most pressing harms are those that already exist or are likely in the near future, such as bias and misuse.

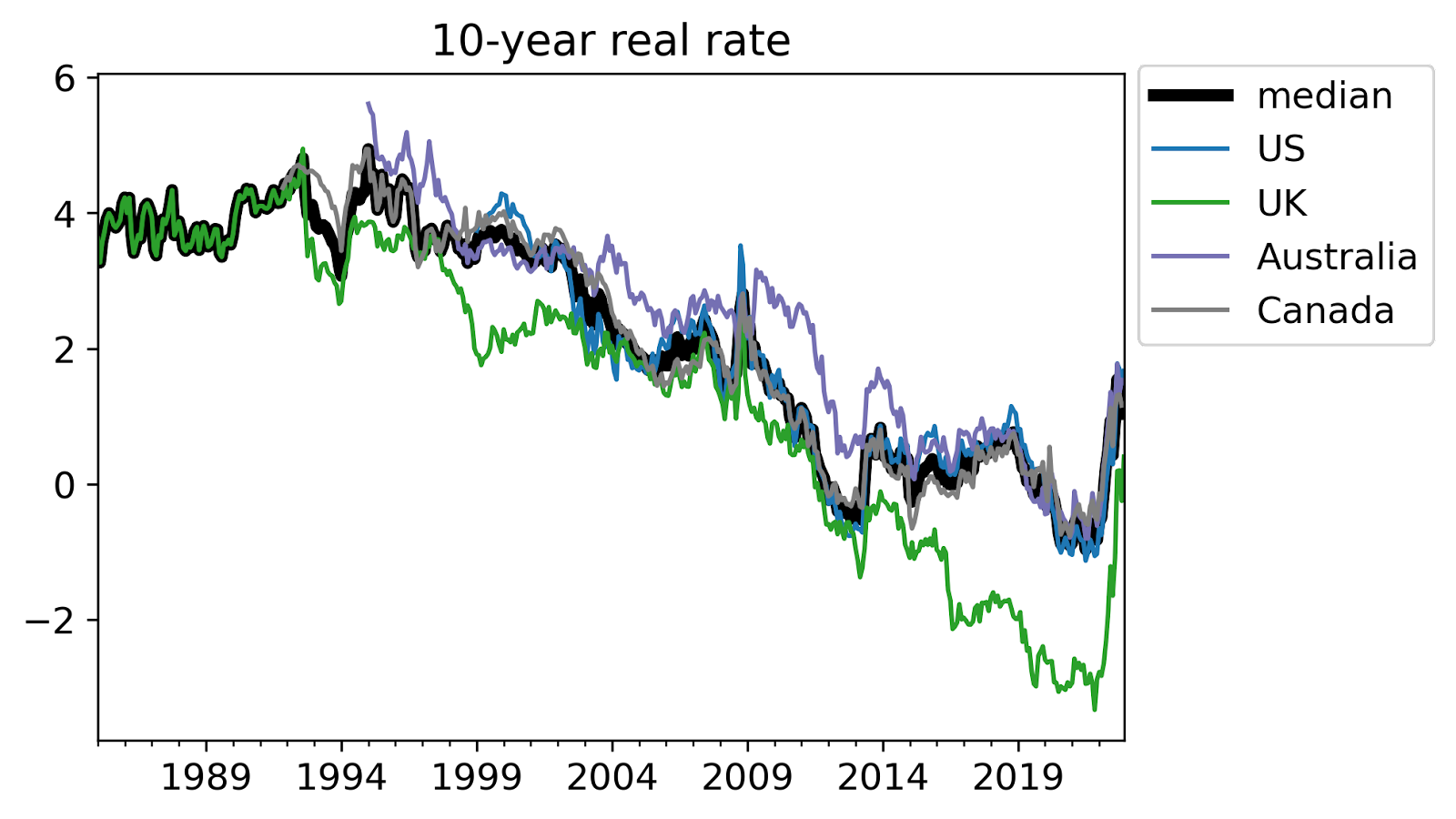

Do not over-index future expectations of growth on progress in one domain. The theory of bottlenecks suggests casting a wide net, tracking progress across many domains of innovation, not just progress in AI’s star subfield. Markets agree. If transformative AI were coming soon, real interest rates would rise in line with expectations of great future wealth or risk. Yet Chow, Halperin, and Mazlish test exactly this theory and find that 10-, 30-, and 50-year real interest rates are low.

Accordingly, invest in the hardest problems across innovation and society. Pause before jumping to the most flashy recent development in AI. From technical research challenges currently not in vogue to the puzzles of human relations that have persisted for generations, broad swaths of society will require first-rate human ingenuity to realize the promise of AI.

The authors: Arjun Ramani is the global business and economics correspondent at The Economist. Zhengdong Wang is a research engineer at Google DeepMind. Views our own and not those of our employers.

We are grateful to Hugh Zhang for excellent edits. We also thank Will Arnesen, Mike Webb, Basil Halperin, Tom McGrath, Nathalie Bussemaker, and Vijay Viswanathan for reading drafts, and many others for helpful discussions.

-

See the discussion between Tom Davidson and Ben Jones in Jones’s review of Davidson, which we note is probably the best countercase to our arguments. ↩

-

Baumol and the economist William Bowen famously used the Schubert string quartet as an example of a stagnant sector for which labor remained essential. The exact numbers for how much growth in one sector contributes to aggregate growth depends on the price and income elasticities of demand for the outputs of both sectors. ↩

-

Acemoglu, Autor, and Patterson provide numerous historical examples of bottlenecking: “breakthroughs in automotive technology cannot be achieved solely with improvements in engine management software and safety sensors, but will also require complementary improvements in energy storage, drivetrains, and tire adhesion… when some of those innovations, say batteries, do not keep pace with the rest, we may simultaneously observe rapid technological progress in a subset of inputs and yet slow productivity growth in the aggregate.” ↩

-

A similar concept exists in computer science. Gustafson’s law shows that sequential tasks set theoretical limits on the gains from parallel computing (though one can of course use the leftover parallelizable resources to complete other tasks). ↩

-

Matt Clancy most recently discusses the idea of bottlenecking in a debate with Tamay Besiroglu in Asterisk Magazine. ↩

-

A caveat here. The problem arises when sequence models condition on their past outputs to produce new outputs, such as imitating an expert policy when learning from offline data. Online reinforcement learning treats agent actions as causal interventions and is one way to solve this problem. But this returns us to the sample efficiency and deployment challenges of reinforcement learning. At the moment it seems we can fully reap the benefits of only one of massive pre-training and interactive decision-making. Integrating causality into AI research is a project whose champions include Yoshua Bengio. ↩

-

Erik Brynjolfsson makes a related point in his essay “The Turing Trap.” If the ancient Greeks had built automatons that could perform all work-related tasks from herding sheep to making clay pottery, labor productivity would certainly go up. But the living standards of ancient Greeks would still be nowhere where they are today. That requires technology that can perform tasks humans were never able to do in the first place. It is certainly plausible that AI does this (in fact it already has in some domains). But the thought experiment does suggest that producing “human-like” AI may not by itself radically boost productivity growth. ↩